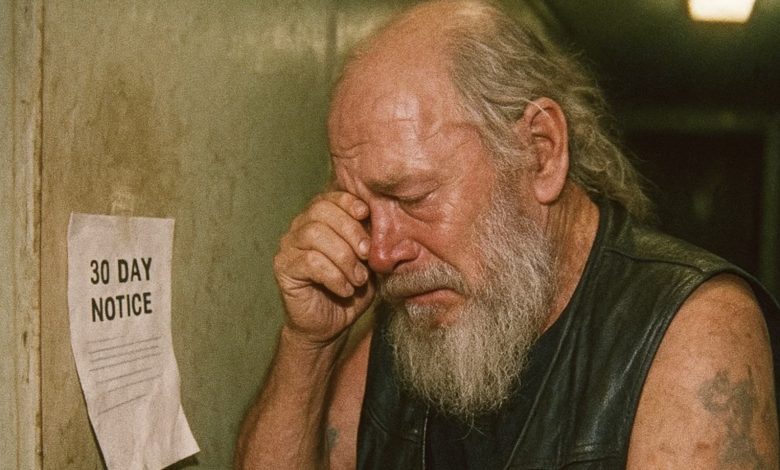

My Landlord Evicted Me After 40 Years Because Old Bikers Like Me Ruin Their Property Values

I never thought I’d face eviction at 72 years old just for being an “intimidating old biker,” but after 40 years in the same apartment building, the new corporate landlords decided my Harley in the parking lot and my leather cut and combat tattoos were “lowering property values” and “making other tenants uncomfortable.”

Three tours in Vietnam, a spotless rental history, and not even one noise complaint in four decades meant nothing once that luxury development company bought our building. They couldn’t legally evict me for being a biker—so they doubled my rent instead, knowing damn well my fixed Social Security income couldn’t stretch that far.

Yesterday, I received the final notice pinned to my door: “Vacate within 30 days.” As I stood there, leaning on my cane—the same leg that took shrapnel in Khe Sanh giving out a little more each year—my neighbor Martha whispered, “They’re doing it to all the old people, but they started with you because they think no one will stand up for some scary old man with tattoos.”

Fifty years ago, I would’ve handled this differently. Back then, brothers from the motorcycle club would’ve paid those corporate suits a visit they wouldn’t forget. But those days are long gone—most of my riding brothers are now dead or in nursing homes. I’m the last one still independent, still riding whenever my leg permits, still proudly wearing the leather cut that shows where I’ve been and what I’ve survived.

Now, at 72, I face living in my van because society still sees an old biker as disposable—someone whose dignity doesn’t matter, whose service counts for nothing if it comes wrapped in leather and tattoos. I spent my life fighting for freedom overseas and working honest jobs here at home, but apparently, that’s not enough to deserve a roof over my head in my final years.

The worst part isn’t losing my home—it’s realizing that after all this time, I’m still judged solely by my appearance rather than by the man I actually am. And at my age, I’m too damn tired to start over again.

The eviction notice had been printed on expensive paper, the kind with the company watermark and embossed logo. So damn official-looking. “NOTICE TO VACATE.” Thirty days to leave the place I’d called home since I’d come back from my third tour with a Purple Heart and a leg full of shrapnel.

I stood in my living room, surrounded by forty years of life. The small bookshelf packed with paperbacks. The wall of photographs—me and the boys from the 173rd Airborne Brigade, me on my first Harley in ’73, my riding brothers from the Veterans Motorcycle Club, weathering from young men to old ones across decades of captured moments. The worn leather recliner where I’d spent countless evenings.

How the hell do you pack up forty years in thirty days? Especially when there’s nowhere to pack it to?

The rent increase notification had come three months earlier. My $850 apartment—already stretching my budget—would now cost $1,700. An impossible sum on my Social Security check. I’d gone to the management office immediately, thinking there must be some mistake.

The new property manager—young woman with a sleek haircut and clothes that probably cost more than my monthly income—had smiled without warmth.

“I understand your concern, Mr. Rawlins, but Brighton Capital has substantial renovations planned. The new rent reflects the future market value of the upgraded units.”

“I’ve lived here forty years,” I’d explained, leaning heavily on my cane. “Never missed a payment, never caused trouble. Doesn’t that count for something?”

Her eyes had flickered to my weathered leather vest with its Veterans MC patch, the POW/MIA emblem, the faded tattoos visible beneath my shirt sleeves.

“We’re offering the same terms to all current tenants,” she’d said, her tone making it clear the conversation was over.

But I knew better. The “same terms” were designed to clear out certain tenants—the ones on fixed incomes, the elderly, the disabled. The ones who didn’t fit the sleek new image Brighton Capital envisioned for “The Residences at Parkview” (the pretentious new name for our humble Parkview Apartments).

I’d started looking for another place immediately, but the truth hit hard: there was nothing in my price range anymore. Not in this town where I’d spent my entire post-Vietnam life. Cheaper places had waiting lists years long. Senior housing was full. And nobody wanted to rent to a 72-year-old man on Social Security, especially one who looked like me.

As the deadline approached, panic set in. I’d sold my extra gear—tools, spare motorcycle parts, anything that might bring in cash. I’d inquired about rooms to rent, extended-stay motels, even temporary veteran housing programs.

Nothing.

Which led to this moment—standing in my living room with an eviction notice in my trembling hand, facing the unthinkable. At 72, I was about to be homeless.

The knock on my door startled me from my thoughts. Probably the property manager with some new paperwork, some new humiliation. I opened it, ready to tell them where they could shove their notice.

Instead, I found Martha from down the hall—a retired school teacher in her late 60s—with what looked like half the building’s residents behind her.

“Charlie,” she said without preamble, “we know what they’re doing to you. And we’re not going to let it happen.”

I stared at the unlikely gathering. Besides Martha, there was Raj, the retired engineer from 3B. The Rodriguez family from the first floor. Old Mr. Chen who barely spoke English. The young couple from across the hall who I’d rarely spoken to beyond a passing nod.

“What’s all this about?” I asked, confused.

“It’s about fighting back,” Martha said firmly. “May we come in?”

Still bewildered, I stepped aside, allowing this strange delegation to file into my apartment. There weren’t enough seats for everyone, so many remained standing, looking around with curious eyes at the home of the “scary biker” they’d lived alongside for years.

Young Mrs. Rodriguez—Elena, I remembered—spotted the framed photo of me in uniform.

“You were in Vietnam?” she asked, surprised.

“173rd Airborne,” I confirmed. “Three tours.”

“My father was in Vietnam,” she said softly. “He never talked about it.”

“Most of us don’t,” I replied.

Martha cleared her throat, bringing the focus back. “Charlie, we’ve all received rent increases. Not as high as yours, but enough to force many of us out eventually. They started with you because…”

“Because I’m the easiest to get rid of,” I finished for her. “Old man on a motorcycle. Nobody’s going to rally around someone like me.”

“That’s what they thought,” Martha agreed. “But they were wrong. We’ve been neighbors for years, Charlie. We’ve seen how you help Mr. Chen carry his groceries when his arthritis is bad. How you fixed the Rodriguez’s car when it wouldn’t start. How you sit with Raj on the anniversary of his wife’s death so he won’t be alone.”

I shifted uncomfortably. I wasn’t used to people talking about these things. They were just what neighbors did for each other.

“What’s your point?” I asked gruffly.

“Our point,” Raj spoke up, his voice still carrying traces of his native India after fifty years in America, “is that we know who you are beneath the motorcycle vest and the tattoos. And we’re not going to let them push you out because of how you look.”

Martha nodded. “We’ve been doing research. Brighton Capital has been buying up buildings all over the city, using the same tactics. Massive rent increases targeted first at the most vulnerable or ‘undesirable’ tenants, followed by cosmetic renovations and rebranding to attract wealthy young professionals.”

“And what exactly do you think we can do about it?” I asked. “They own the building. They can charge what they want.”

“Not necessarily,” said the young man from across the hall—Tim, I recalled. “I’m a law student. There are tenant protection laws they may be violating, especially regarding discrimination against protected classes.”

“Being a biker isn’t a protected class, son,” I said with a bitter laugh.

“No, but being a senior citizen and a disabled veteran is,” he replied evenly. “And if we can prove they’re specifically targeting you because of your age or veteran status, disguised as aesthetic concerns about your motorcycle or appearance, we might have a case.”

Hope flickered briefly before reality doused it. “Even if that’s true, I can’t afford a lawyer. And a lawsuit would take months or years. I’ve got thirty days.”

“That’s why we’re here,” Martha said. “First, we’re organizing as a tenants’ association. Strength in numbers. Second, Tim has contacted a housing rights clinic that provides pro bono legal services. Third,” she paused, looking slightly uncomfortable, “we’ve started a community fund to help cover your rent while we fight this.”

Pride rose up in me like a physical force. “I don’t take charity.”

“It’s not charity,” Raj said firmly. “It’s community. It’s what neighbors do.”

“And fourth,” Martha continued, undeterred, “we need your help reaching out to your motorcycle club. We need visibility, public pressure. These corporate types hate bad publicity.”

I stared at them, these neighbors I’d lived alongside for years but never truly known. People I’d helped in small ways without thinking, now standing in my living room offering to fight for me.

“The club isn’t what it used to be,” I said quietly. “Most of the original members are gone now. The younger guys… they do their own thing.”

“But they respect you,” Martha insisted. “Elena’s husband works at the local news station. We want to tell your story—decorated Vietnam veteran, model tenant for forty years, being pushed out because he rides a motorcycle and doesn’t fit their ‘upscale image.’ We want your motorcycle friends there when we tell it.”

The thought of being a public spectacle made me deeply uncomfortable. I’d spent decades being stared at, judged for my leather and tattoos. The idea of deliberately putting myself in the spotlight went against every instinct.

But the alternative was worse. Living in my van. Losing the home where I’d rebuilt my life after Vietnam. At my age, with my health issues, it could be a death sentence.

“Let me think about it,” I finally said.

Martha nodded, understanding my reluctance. “We’ll meet tomorrow evening in the community room to organize. Please come, Charlie. We need you as much as you need us.”

After they left, I sat heavily in my recliner, overwhelmed by what had just happened. In all my years of riding, the code had always been clear: you handle your own problems, you don’t burden others, and you sure as hell don’t become a cause célèbre.

But maybe, at 72, it was time for new rules.

I reached for my phone and made a call I’d been avoiding.

“Hey, Johnny,” I said when a familiar voice answered. “It’s Charlie Rawlins. I need to ask a favor from the club.”